I. Introduction – Affirmative Defenses for Employing Offices

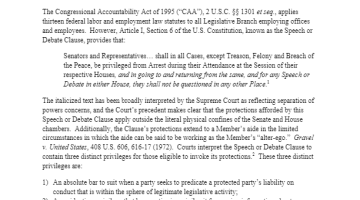

The Congressional Accountability Act of 1995 (“CAA”), 2 U.S.C. §§ 1301 et seq., applies thirteen federal labor and employment law statutes to all Legislative Branch employing offices and employees. However, Article I, Section 6 of the U.S. Constitution, known as the Speech or Debate Clause, provides that:

Senators and Representatives… shall in all Cases, except Treason, Felony and Breach of the Peace, be privileged from Arrest during their Attendance at the Session of their respective Houses, and in going to and returning from the same, and for any Speech or Debate in either House, they shall not be questioned in any other Place.1

The italicized text has been broadly interpreted by the Supreme Court as reflecting the separation of powers concerns, and the Court’s precedent makes clear that the protections afforded by this Speech or Debate Clause apply outside the literal physical confines of the Senate and House chambers. Additionally, the Clause’s protections extend to a Member’s aide in the limited circumstances in which the aide can be said to be working as the Member’s “alter-ego.” Gravel v. the United States, 408 U.S. 606, 616-17 (1972). Courts interpret the Speech or Debate Clause to contain three distinct privileges for those eligible to invoke its protections.2 These three distinct privileges are:

- An absolute bar to suit when a party seeks to predicate a protected party’s liability on conduct that is within the sphere of legitimate legislative activity;

- An evidentiary privilege that bars parties in a civil suit from using information about a “legislative act” against a party protected by the Clause; and

- A testimonial privilege (and in some Circuits, a non-disclosure privilege) that protects Members of Congress from being compelled to answer questions about legislative acts, even if the Member is not a party to the suit.